Seeing a subterranean animal any naturalist finds it difficult not to wonder about evolutionary processes that shaped it. However, the value of these animals reaches far beyond pure naturalist curiosity. Many of them are excellent models for studying evolutionary processes, as they are replicated across different karst regions and live in an environment with strong directional selection pressures. Neutral mutations, selection-driven adaptations to extreme subterranean environment, pleiotropy, dispersal through the network of human-inaccessible voids and speciation following colonization of the subterranean environment, are some of the topics that have enriched our understanding of evolution in general. We exploit these processes at three partially overlapping levels.

Crossing the Styx: adaptation and speciation

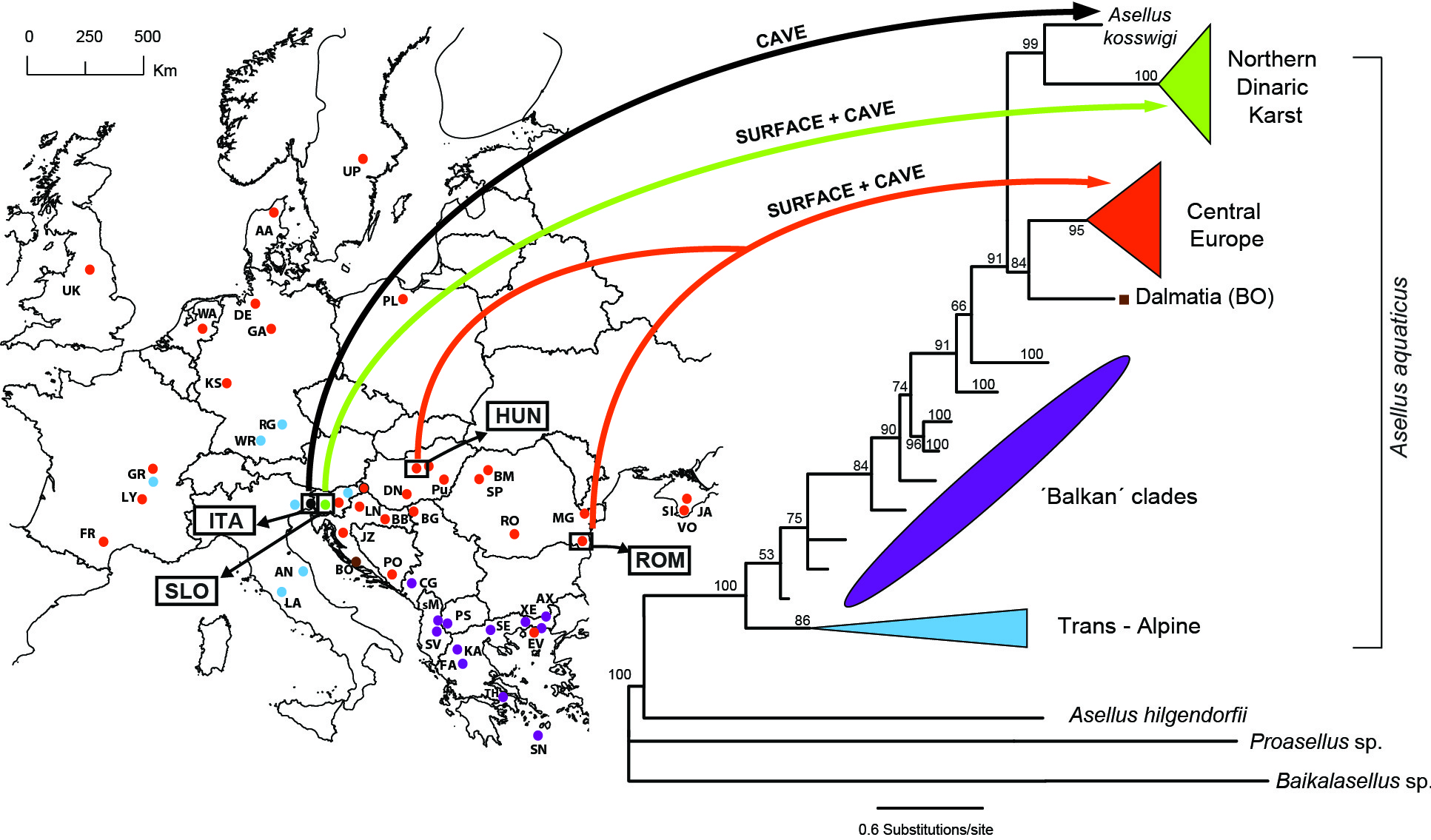

Species entering the subterranean realm are subdued to a dramatic environmental change. Who were the early colonizers? A random subsample of surface populations? Individuals with behavioral and/or morphological advantages? What evolutionary processes drive loss of pigment and eyes – neutral mutations, selection, or both? Have similar phenotypes evolved through same or different evolutionary processes? How has the evolution of behavioral traits interacted with evolution of morphology? Has ecological adaptation to the subterranean environment caused the cessation of gene flow between surface and subterranean populations? We study these and other questions on Asellus aquaticus, a freshwater isopod crustacean with independently replicated surface and subterranean populations by combining comparative methods with experimental work.

Phylogeography of subterranean populations

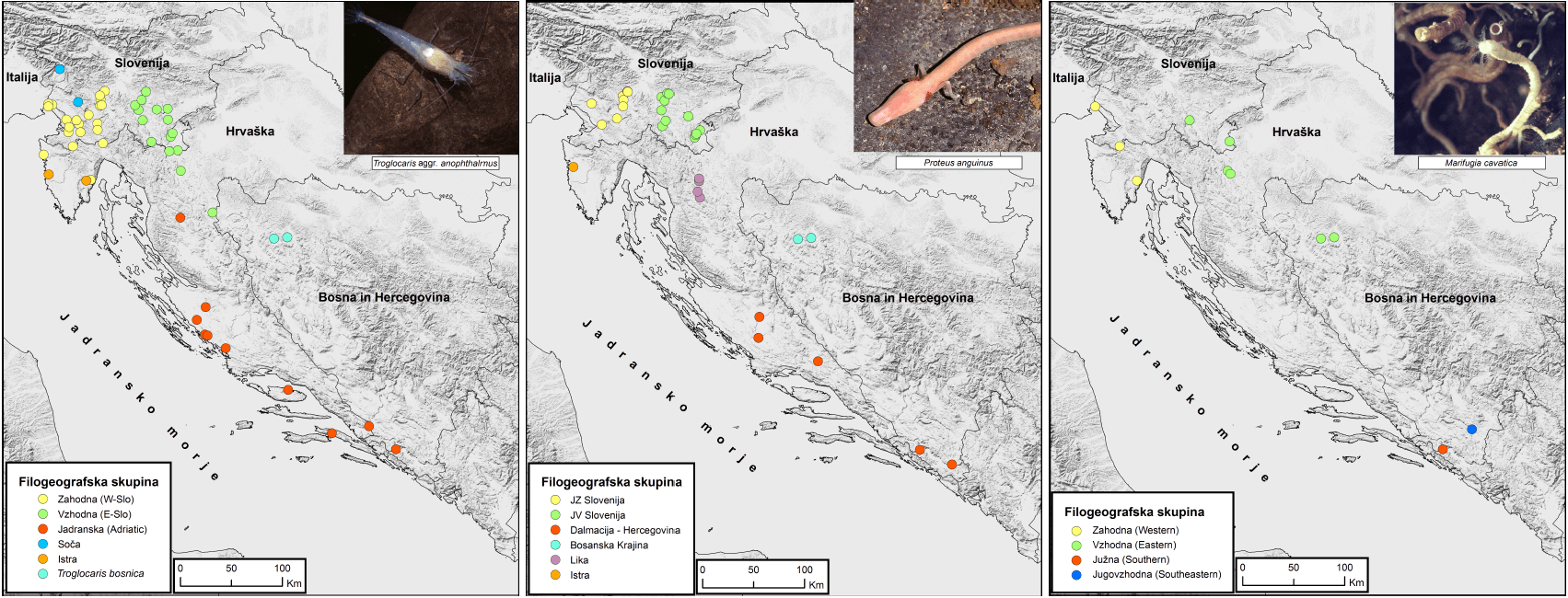

Subterranean environment is highly fragmented and connectivity between populations is naturally restricted. Did these natural conditions affect different subterranean species similarly? Can we expect shared phylogeographic patterns? What present and past factors have shaped phylogeographic patterns, and how has evolutionary history affected the genetic diversity of subterranean species? Using combined, molecular-spatial models, such questions have been applied to a number of metazoans from the Dinaric Karst, including the cave shrimps Troglocaris, the tube-worm Marifugia and the olm Proteus anguinus.

Dinaric Karst harbors many charismatic and interesting species. Many of them presumably live along the entire mountain massive. Phylogeographic analyses have shown that each of these species comprises a number of morphologically cryptic species with a superficially similar phylogeographic pattern. Left: Marifugia cavatica species complex, middle: Troglocaris anophthalmus species complex, right: Proteus anguinus species complex.

Diversification within the subterranean realm

The subterranean environment is not a dead end; evolution vividly continues within it. Some species evolve without morphological change, whereas other species differ strongly from each other. What processes and what circumstances have determined the phenotypes of descending species? Has subterranean diversity evolved continuously over time, or has it evolved in a few diversification bursts? We study these evolutionary changes through reconstruction and comparative approaches, using the amphipod genus Niphargus, the isopod genus Monolistra and beetle families Cholevidae and Trechinae.